Global learning, local impact: elevating renewable energy training through cultural intelligence

July 2025

As the Global Wind Organisation (GWO) drives toward ‘Excellence in Quality’ and ‘Leading the Industry in Workforce Development’ as part of their 2026 strategic initiatives, it is important for the renewables sector to consider what it means to deliver training that is truly global.

With over one hundred and forty-three thousand people trained in GWO training courses in 2024 alone across over 36 countries, and those numbers rising year on year, the challenge is not just about access to training but about ensuring that the training standards and expectations are the same the world over. Training must be globally transferable, relevant, effective, and importantly, culturally attuned. Learning and Development (L&D) can be made truly global by embracing cultural diversity, leveraging technology, and aligning with GWO’s strategic goals.

Making training global while looking beyond a one-size-fits-all approach

In today’s interconnected world, global training programs are more essential than ever. However, a common pitfall is the assumption that a training session delivered in Aberdeen will be just as effective in Azerbaijan. This overlooks critical contextual differences, ranging from available equipment and learner expectations to cultural norms and communication styles.

True global training isn’t about identical delivery or the illusion of uniformity, it’s about ensuring consistency in quality and outcomes while adapting to local realities. By acknowledging and respecting these differences, organisations can create learning experiences that are both globally aligned and locally relevant, ultimately driving better engagement, retention, and performance.

As organisations expand across borders, the need for culturally intelligent training becomes increasingly vital. A common misstep in global learning strategies is assuming that one-size-fits-all content will resonate equally across diverse regions. In reality, effective global training requires thoughtful flexibility.

To accommodate cultural differences, training programs must go beyond simple translation. This means localising delivery with culturally relevant examples, adapting delivery styles to suit local learning preferences, and being mindful of communication norms. The goal isn’t to tick cultural boxes but to foster genuine engagement while maintaining the integrity of the learning outcomes.

Respecting local customs while upholding global standards is a delicate balance, but it’s one that pays dividends. When learners feel seen and understood, they are more likely to connect with the material, apply it effectively, and contribute to a stronger, more inclusive global workforce.

Culture and learning

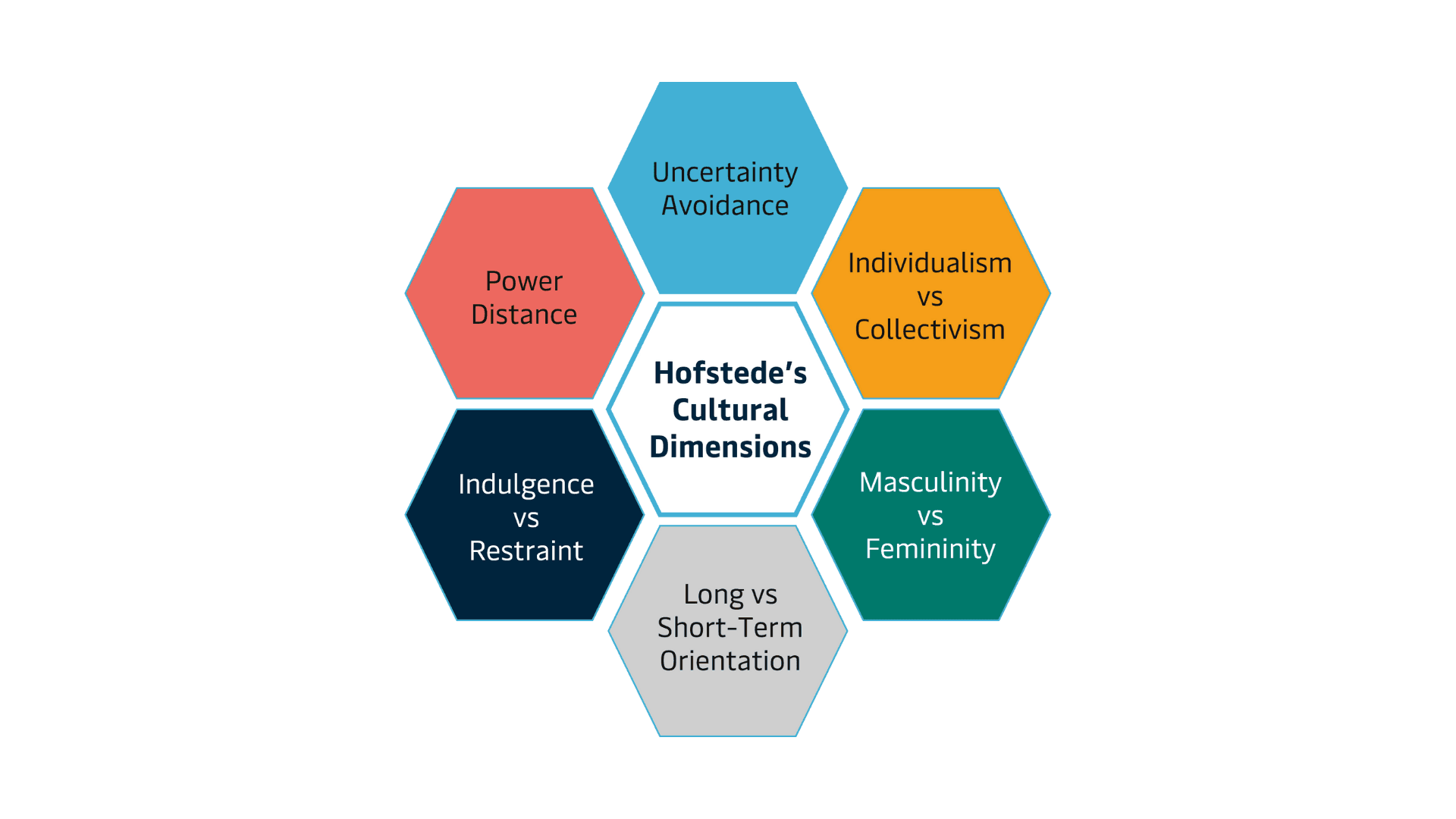

In understanding some of the cultural challenges in making training truly global, frameworks such as Hofstede’s national cultural framework are useful tools in comprehending the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of differentiated learning related to cultural variances.

Fig.1. Hofstede National Culture Dimensions

The framework can uncover how deeply national culture influences learning. It can provide insight into how training could be altered to give the best learning experience for the people in those different geographical locations.

Taking Maersk Training’s global training centres for example, the framework provides insight into how national cultural norms and behaviours could impact learning. For example, the UK and Denmark tend to have low power distance which is the extent to which power is shared among members of society. Lower power distance indicates less relevance of hierarchy while valuing autonomy, independence and an expectation that information is shared, and people are consulted in decisions regardless of their position. This means that culturally, power between trainers and learners is shared more equally. This results in a flatter hierarchical relationship which is likely to encourage more open dialogue, increase classroom discussions and promote questioning between trainers and learners. Learners may expect to be able to challenge ideas in informal learning environments.

In contrast trainers in Brazil and Saudi Arabia should consider a higher power distance, where learners may defer to authority and hierarchy and expect stricter structural guidance on performance. In training, this could result in less balanced dialogue and delegates being more likely to expect an instructor-led approach as opposed to a collaborative approach where delegates have some element of ownership of their learning. This deep-rooted respect for authority may mean a structured, formal training environment is preferred and generates better results and outcomes.

These cultural differences are best considered, not by the content of material, but by the expertise and local appreciation of the instructor.

As well as power-distance norms within cultures, Hofstede’s work identifies various cultural aspects including how cultures manage uncertainty within situations. While Danish culture is happy with unpredictability and ambiguous situations drawing on curiosity to navigate diversions in plans and structures, Japan and Brazil thrive where there are strong rules, structures and expectations of what lies ahead. Again, these differences will affect how the learner engages with the content from the very beginning. Danish learners will likely thrive in fluid situations where the instructor is agile and reacts to the ability of the delegates tailoring the training through variations in structure and language where necessary, while Brazilian and Japanese learners will thrive in understanding the clear picture and moving the training through methodical steps to achieve the clearly stated outcome. If these needs are understood and met, a more appropriate learning environment is created for those specific learners, which again could produce more successful outcomes and a successful learning experience.

It is also important to recognise the cultural differences in the trainer delivering the training and the cultural norms and expectations of them as a trainer. A trainer from a culture where ambiguity is accepted and conducts training in a flexible way in accordance with how the learners are developing, might cause anxiety in Japan for example. Therefore, training design must be consistent in content but flexible in strategy. The ‘what’ of training should always be the same, but the ‘how’ is what truly unlocks learning.

Great training is not robotic. While consistency is important, trainer individuality through stories, anecdotes, and contextualisation enhances learning. Trainers must be empowered to deliver content to their audience using their own experience and expertise while preserving the core message, core outcomes and required quality.

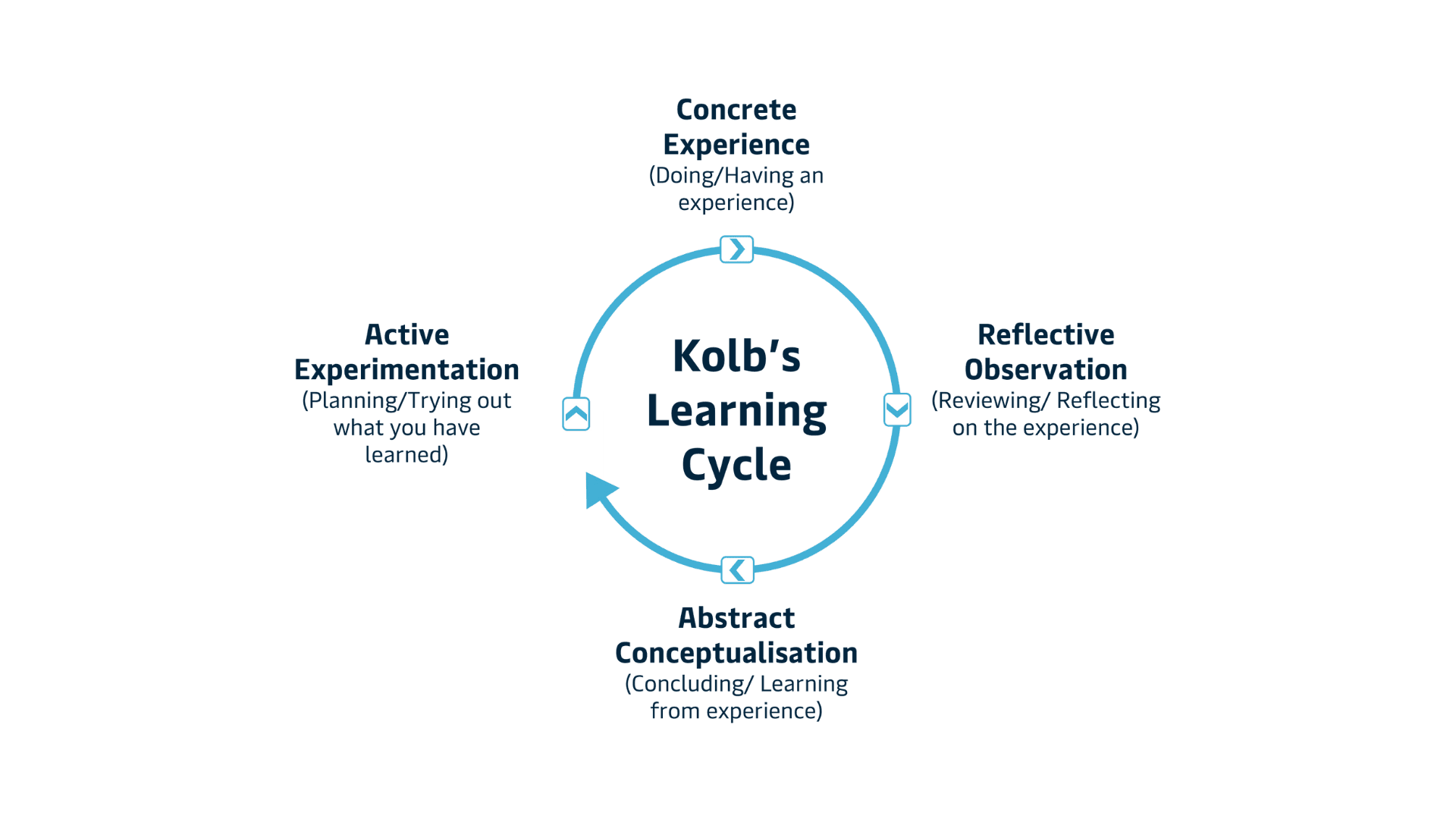

Fig.2. Kolb’s Learning Cycle (Taken from GWO Requirements for Training V15)

The GWO references David Kolb’s learning cycle as a useful tool in illustrating different phases of the learning process and signifies the importance of ‘Active participation’ in all aspects of practical training, reflection and expressing understanding. This is also another useful model for appropriating the most desired learning methods based on the cultural aspects of the learners. In Kolb’s more recent research (Are there cultural differences in learning style? J. Soy & D.A. Kolb, 2009), it is noted that culture can have an impact in affecting someone’s preference for abstract conceptualisation compared to concrete experience for example. However, it is also noted that level of education and particularly one’s area of specialisation have significant impact on how individuals prefer to learn, thus adding credence to the importance of understanding each group of learners across locations and therefore adjusting the ‘how’ in order to meet learner needs.

Applying global standardisation and national differences

An important factor in applying these cultural differences is to identify where similarities in training must happen and cannot be compromised on. Those are the fundamentals of the training: the aims, learning objectives and the desired outcomes at the expected standard.

The cultural adaptations should happen through effective classroom and learner management, teaching methods, and a learning-centred approach in understanding the cultural norms, expectations and unconscious biases towards one learning approach or another.

It is important to have policies, procedures and norms that respect the understanding of the need for centralised training. It allows more cohesive updates, makes auditing more centralised and controlled while eliminating national differences in audit procedures and expectations. This is one way of ensuring the expected standards are achieved and delivered at the expected level. As good as any standard or procedure is, it is only as good as one’s perception of how it should be implemented. Perceptions of expectations differ individually because of biological, psychological and environmental factors. This is something that is seen in training centres and education facilities even within the same country or facility. Adding cultural differences in perception due to learned behaviours, beliefs and values can distance the perception of a standard or way of working even further.

The Maersk Training approach

Maersk Training delivers global training with local relevance. Our strategy includes centralised content with the flexibility for national differences through oversight by globally minded L&D managers, and a unified 'Maersk Training Voice'. Customers and clients can be sure that sending an individual to complete working at height training in Brazil will produce the same standard of trained individual as sending them to Denmark. This flexibility stems not from the lesson plan or the presentation, but from the individual trainer. Their skill and experience are what provides them the ability to contextualise content in a way that meets individual learners needs and enhance learning.

Maersk Training is also continuing to expand our blended learning portfolio which is a key component in ensuring training is accessible around the globe. Delegates complete theoretical modules online, then attend local centres for practical training. Centralising the theoretical content again ensures that someone completing the learning in Japan is experiencing the same content as a colleague in the UK. Where localised national culture and contextualisation is in the practical training at their local training centre.

This approach not only ensures consistency in theoretical knowledge but also respects and adapts to local cultural nuances during practical application. By centralising the digital content, we maintain high standards and alignment with global best practices. At the same time, the localised delivery of hands-on training allows us to tailor the experience to regional expectations, languages, and safety regulations, ensuring relevance and resonance with learners on the ground.

Blended learning, in this context, becomes more than a delivery method, it becomes a strategic enabler. It allows us to scale training across continents while maintaining the flexibility to adapt to local needs. This is particularly important in the renewables sector, where teams often operate in remote or culturally diverse environments, and where safety-critical knowledge must be both universally understood and locally applicable.

References

-

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

-

Hofstede, Geert (2001). Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. SAGE Publications.

-

Joy, S. & Kolb, D.A. (2009). Are there cultural differences in learning styles? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(1), pp.69-85